Authorization Before Retrieval: Making RAG Safe by Construction

Summary: Retrieval-augmented generation makes language models far more useful by grounding them in real data, But it also raises a hard question: who is allowed to see what? This post shows how authorization can be enforced before retrieval, ensuring that RAG systems remain powerful without becoming dangerous.

In the last three posts, I’ve been working toward a specific architectural claim. First, I argued that AI is not—and should not be—your policy engine, and that authorization must remain deterministic and external to language models. I then showed how AI can still play a valuable role in policy authoring, analysis, and review, so long as humans remain responsible for intent and accountability. Most recently, I explored how AI can help us understand what our authorization systems actually do, surfacing access paths and assumptions that are otherwise hard to see. This post completes that arc. It takes the conceptual architecture from the first post and makes it concrete, showing how authorization can shape retrieval itself in a RAG system, ensuring that language models never see data they are not allowed to use.

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has quickly become the default pattern for building useful, domain-specific AI systems. Instead of asking a language model to rely solely on its training data, an application retrieves relevant documents from a vector database and supplies them as additional context in the prompt. Done well, RAG allows you to build systems that answer questions about your own data—financial reports, customer records, engineering documents—without the expense of creating a customized model.

But RAG introduces a hard problem that is easy to gloss over: who is allowed to see what.

If you are building a specialized AI for finance, for example, you may want the model to reason over budgets, forecasts, contracts, and internal reports. That does not mean every person who can ask the system a question should implicitly gain access to every financial document you’ve vectorized for the RAG database. RAG makes it easy to retrieve relevant information, but does not, by itself, ensure that retrieved information is authorized.

This post explains how to do that properly by treating authorization as a first-class concern in RAG, not as a prompt-level afterthought.

A Quick Review of How RAG Works

In a basic RAG architecture:

Documents from the new, specialized domain are broken into chunks and vectorized.

Those vectors are stored in a vector database along with any relevant metadata.

When a user submits a query, the system first embeds it, converting the text into a numerical vector that represents its semantic meaning. It then:

retrieves the most relevant chunks,

inserts those chunks into the prompt,

and asks the language model to generate a response.

This pattern is widely documented and well understood (see OpenAI, AWS, and LangChain documentation for canonical descriptions). The key point is that RAG adds system-selected context to the prompt, not user-provided context. The application decides what additional information the model sees.

That is exactly where authorization must live.

The Problem: Relevance Is Not Authorization

Vector databases are excellent at answering the question “Which chunks are most similar to this query?” They are not designed to answer “Which chunks is this person allowed to see?”

A common but flawed approach is to retrieve broadly and then rely on the prompt to constrain the model, saying, essentially:

“Answer the question, but do not reveal confidential information.”

This does not work. Prompts describe intent; they do not enforce authority. If sensitive data is included in the prompt, it is already too late. The model has seen it.

If you are building a finance-focused AI, this becomes dangerous quickly. A junior analyst asking an innocuous question could trigger retrieval of executive compensation data, merger documents, or board-level financials simply because they are semantically relevant. Without authorization-aware retrieval, relevance collapses access control.

Authorized RAG: Authorization Before Retrieval

The correct approach is to ensure that authorization constrains retrieval itself, not just response generation.

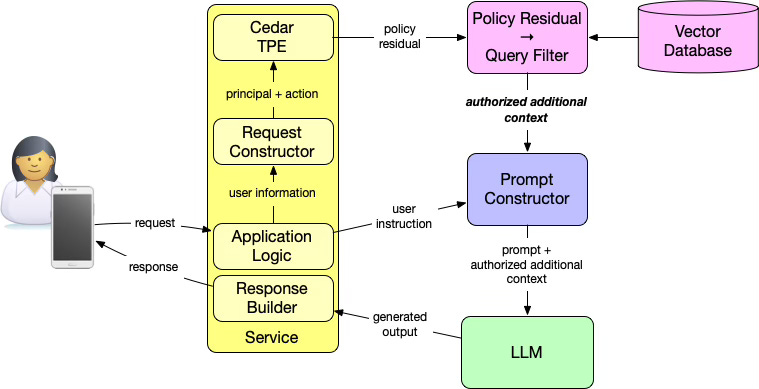

The diagram above shows how this works in an authorized RAG architecture. At a high level:

The application evaluates authorization for the principal (who is asking) and the action (for example, “ask a question”).

Cedar’s type-aware partial evaluation (TPE) evaluates the authorization policy with an abstract resource and produces a policy residual.

That policy residual is a constraint over resources providing a logical expression that describes which resources may be accessed.

The application compiles that residual into a database-native query filter.

The vector database applies that filter during retrieval.

Only authorized additional context is returned and included in the prompt.

The language model never decides what it is allowed to see. It only operates on context that has already been filtered by policy. This is the critical shift: authorization shapes the world the prompt is allowed to explore.

Cedar TPE and Policy Residuals

Cedar’s type-aware partial evaluation is what makes this architecture practical. Instead of fully evaluating policies against a specific resource, TPE evaluates them with an abstract resource and produces a policy residual representing the remaining conditions that must be true for access to be permitted. Importantly, that residual is type-aware: it references concrete resource attributes and relationships defined in the schema.

The Cedar team has written about this capability in detail, including how residuals can be translated into database queries. While TPE is still an experimental feature, it is already sufficient to demonstrate and build this pattern.

From an authorization perspective, the residual is not a decision. It is not permit or deny. It is a constraint over resources that the application can enforce however it chooses.

Vectorization, Metadata, and Filtering

For this to work, vectorized data must carry the right metadata. Each embedded chunk should include:

tenant or organizational identifiers,

sensitivity or classification labels,

relationship-based attributes (teams, owners, projects),

anything the authorization policy may reference.

Once Cedar TPE produces a policy residual, that residual can be compiled into a filter expression over this metadata. In Amazon OpenSearch, for example, this becomes a structured filter applied alongside vector similarity search. Relevance scoring still happens but only within the authorized subset of data.

This is not heuristic filtering. It is deterministic enforcement, just expressed in database terms.

A Concrete Example (and a Working Repo)

To make this tangible, I’ve published a working example in this GitHub repository. The repo includes:

a Cedar schema and policy set,

example entities and documents,

vector metadata aligned with policy attributes,

and a Jupyter notebook that walks through:

partial evaluation,

residual inspection,

and residual-to-query compilation.

The notebook is deliberately hands-on. You can see the policy residual produced by Cedar, inspect how it constrains resources, and observe how it becomes a vector database filter. Nothing is hidden behind abstractions. This is not production code, but it is runnable and concrete. The repository provides a working demonstration of how authorization can be used to filter enhanced context in RAG.

Why This Matters

RAG systems are powerful precisely because they blur the boundary between static models and dynamic data. That same power makes them dangerous if authorization is treated as an afterthought.

Authorized RAG restores a clear separation of responsibility by design:

Authorization systems decide what is allowed.

Databases enforce which data may be retrieved.

Prompts express intent, not policy.

Language models generate responses within boundaries they did not define.

RAG becomes defensible only when authorization reaches all the way into retrieval, translating policy into constraints that databases can enforce directly. In a well-designed RAG system, authorization doesn’t shape the prompt; it shapes the world the prompt is allowed to explore.

Photo Credit: Happy computer ingesting filtered data from DALL-E (public domain)